This raises an interesting question in the philosophy of wellbeing. Opossums are (plausibly) prudential subejcts: things can go well for an opossum, or poorly for her. Opossums have mental states—they can experience (dis)pleasure and have preferences—, and, if humans have a telos, so (perhaps) do opies. (It would be a peculiar datum indeed that there be human-relevant prudential properties without this being so of similar enough beings.)

Cucumbers, on the other hand, are not prudential subjects. Nothing can go well for a cucumber, and they cannot be harmed. They have no desires or phenomenal states or proper function. They are cucumbers.

When things are going well for a subject, her wellbeing is high; when things go poorly, it is low. We might think that how good things are for a subject depends in part on that subject's relevant capacities; no capacity to desire—no desires—no satisfaction thereof. We might then think that, all else equal, things are better for a human than an opossum, since, e.g., humans (perhaps!—opies are clever) have richer mental lives.

The upshot of this view for the cucumber (or any other nonsubject) is that they 'have' a wellbeing level of zero: no prudential capacities, no desires nor preferences to be satisfied or frustrated, nor pleasure nor pain nor knowledge nor friendship nor spirituality.

You might think that to suggest that cucumbers 'have' a level of wellbeing at all is a total nonsense, like speculating as to what rocks dream about. But there are two ways to have null content in your dreams: to dream not about anything, and not to dream. Similarly, when we assign a level of wellbeing zero, this can either be because things are going, on balance, neutrally for a subject, or because there is no subject for things to go well or badly for.

These capacity limit cases, or quasi-wellbeing levels, allow us to compare nonsubjects with subjects by saying, e.g., 'were this cucumber a prudential subject, its level of wellbeing would be zero', and, thus, to assert with J. S. Mill that it's better to be Socrates than a pig—and better a pig than a cucumber!

This raises the question latent in that image macro: is it really better to be an opossum than a cucumber?

The trouble with just saying 'yes' is this: we don't know where zero is; we don't know how good it is to be a cucumber—or what rocks dream about. But there's a sense in which we know exactly how good it is to be a cucumber—we know by stipulation; being a cucumber is zero. We just don't know where this stands in relation to us. Or, to put it another way, we don't know where we are (in relation to the fixed points on the scale); we don't know how good it us to be us.

But what is the upshot of this? We'll briefly consider two.

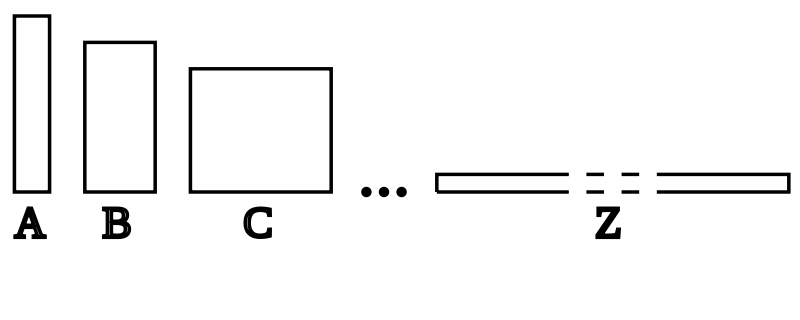

First off, let's consider (20th/21st c. value theorist) Derek Parfit's repugnant conclusion argument. Imagine you have a population A of some arbitrary size; add up all the wellbeing levels of all the people in A to get A's total wellbeing. Now, imagine a population B whose average wellbeing is slightly lower than that of A, but has enough extra people to make the sum of B-people wellbeing, B's total wellbeing, greater than that of A. So B is better than A. But we can imagine a population C that stands to B as B does to A, and a population D that stands to C as C to B, ..., and a population Z which stands to Y as Y to X, and so must be better than A. But everyone in Z has a very low—positive but tiny—level of wellbeing; they are just above zero. So, the thought goes, we should give up total wellbeing as a measure of the wellbeing of a population (since A is better than Z).

It's often implicitly assumed by people that make this argument that we are like the people in population A, but perhaps we are more like the people in Z: perhaps we are not so far above zero than we thought.

Another place the question about where we are in relation to zero raises a problem is questions concerning wellbeing and death. Some arguments for the badness of death (deprivation and comparative accounts) make implicit or explicit reference to dying or being dead having a prudential value of zero, and one's relation to zero.

(Plato's) Socrates, in the Apology, suggests that death as permanent unconsciousness would not be a harm (perhaps—the purpose of this passage is unclear). Even the immensely prudentially well-off Great King, he says, would be unable to find any experience as blissful. Anyone who has taken an midafternoon nap can see the intuitive force of this claim.

George Rudebusch (a contemporary philosopher) analyses this in terms of (20th c. ordinary language philosopher) Gilbert Ryle's distinction between sensate and modal pleasures. Consider the example of the pleasure given by listening to music. There may be some pointed and particular moments of sensate pleasure—an exquisite harmony, an unexpected leap in the melody, an inexplicably catchy hook—but even when these are absent, we are still taking some sort of pleasure from listening to the music, modal pleasure. Were I to ask you whether you enjoyed the piece, you would say 'yes', not 'I enjoyed the piece at these particular times'; you enjoyed the whole piece.

This modal sense is that in which permanent unconsciousness is endless bliss: there is no particular moment at which you take pleasure from your napping—you are asleep—; rather, you enjoy the whole nap, as Socrates enjoys the interminable peace of permanent unconsciousness. (Ryle's golfer takes pleasure in that hole-in-one on hole six, but she also takes pleasure in the whole game.)

If lack of sensation—and, suppose, (dis)pleasure, preference satisfaction/frustration, &c.—is inflected with modal pleasure, what are we to say about 'zero'? Perhaps cucumbers wallow in inexpressible bliss, and colourless green ideas sleep furiously after all.

So, we don't know where we are in relation to zero, and this throws some spanners in some elegant philosophical machines. How to resolve these issues is not altogether clear. As Shakespeare could've said: that is the question, whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take arms against a sea of troubles, and by opposing become a cucumber.